Masters of the Internet Purring Away

It’s finally here. I’ve joked on a number of occasions that I will find a reason to blog about the ‘Internet Cat’ and its magnitude in online (and offline) popular culture, and today marks a great reason to do so. Today is the inaugural Australian International Cat Film Furstival held in Sydney hosted by RSPCA NSW in conjunction with the Walker Art Centre, where the original concept originates from (a glorious concept for a self-professed cat video lurker like myself). In August 2012, the Walker Art Centre (Mineapolis, USA) developed the idea of hosting an Internet Cat Video Festival, primarily as a bit of a joke, but also as a social experiment. The result was 10,000 people gathered together to watch videos of cats.

The notion of people coming together and paying to watch a compilation of videos that they can watch for free at home is intriguing and powerful at best. Take Aigrain’s (2005) idea of positive intellectual rights, the idea that such positive rights will enable a new synergy that rewards creators in the public space, that the extraordinary benefits from a greater plurality of creators will reward creation and innovation. Aigrain suggests moving away from the restrictive path of locking away intellectual rights as social damage. It’s a full circle, an ouroborus of ideas: free user-generated content ⇒ uploaded onto a free platform ⇒ viewed for free = exploitation of intellectual rights and an entitlement of free intellectual property? Incorrect. According to Aigrain, we are witnessing a positive progression for intellectual rights, whereby from this open space of innovation and creation (of free videos) a new innovative idea developed of the Internet Cat Video Festival, which brings back copyright-based remuneration that rewards the creators. Traditional views of intellectual property and ownership are shifting away from modems of control and restriction and are opening into new innovations and notions of remuneration and creation.

The notion of people coming together and paying to watch a compilation of videos that they can watch for free at home is intriguing and powerful at best. Take Aigrain’s (2005) idea of positive intellectual rights, the idea that such positive rights will enable a new synergy that rewards creators in the public space, that the extraordinary benefits from a greater plurality of creators will reward creation and innovation. Aigrain suggests moving away from the restrictive path of locking away intellectual rights as social damage. It’s a full circle, an ouroborus of ideas: free user-generated content ⇒ uploaded onto a free platform ⇒ viewed for free = exploitation of intellectual rights and an entitlement of free intellectual property? Incorrect. According to Aigrain, we are witnessing a positive progression for intellectual rights, whereby from this open space of innovation and creation (of free videos) a new innovative idea developed of the Internet Cat Video Festival, which brings back copyright-based remuneration that rewards the creators. Traditional views of intellectual property and ownership are shifting away from modems of control and restriction and are opening into new innovations and notions of remuneration and creation.

Advertisers have also caught onto the viewer’s active engagement with the Internet cat and developed Catvertising in 2011/2. Although originally a parody, a number of companies have taken this approach, some examples including:

- The Shelter Project, making juxtaposition between the human’s sand box and the cat’s litter box;

- Skittles Touch: Cat, part of their Lick the Rainbow campaign; and,

- My personal favourite is Purina’s ‘A Cat’s Guide to Taking Care of your Human’, which is a type of advertorial developed by BuzzFeed — an internet news media company that challenges the traditional model of print and broadcast journalism.

Buzzfeed itself has used the phenomena of Internet cats throughout its business model: from editorial decisions of having them as a natural source of internet media alongside longform news pieces; internal meeting rooms named after Internet cats; a Cat Internet microsite for cats; and Cat Power, a measurement of your Community ranking in Buzzfeed. Hayes, Singer & Ceppos (2007) explored how the way that information will be sourced and determined will shift to be more consumer-driver rather than the traditional agenda-setting news organisations. There is a “shifting of roles” to a more “social response-ability” of openness and social disclosure, a ‘humanizing of the news’, which BuzzFeed and its unconventional style explore with its fierce focus on digital sharing and engagement amongst users and staff.

According to CBS news, 15 per cent of all internet traffic is connected to cats. There is a universal joy and unity in the Internet Cat. From this sensation of numerous cat videos, there are also the cat celebrities: Henri (le Chat Noir), the existentialist cat; Grumpy Cat, the world’s grumpiest cat; Maru, a Japanese cat who slides into boxes; Lil Bub, the ‘perma-kitten’; and the fictional Nyan Cat. And many more were showcased at the Furstival that showed several short Vine-style videos and longer-style videos of cat(s) and their addictive idiosyncratic behaviour. The question of ‘Why we love Internet Cats so much?’ has been asked widely across the Internet, and a quick Google search comes with a plethora of content asking this very question.

There are theories around: the cats’ cuteness; non-cuteness; their aloof personalities; honest behaviour; emotive expressions; ease of personification; we are in awe of their audacity; a continuity of historical adoration dating back to Ancient Egypt; their exaggerated resemblance to our offspring; and a theory around their ‘unselfconsciousness‘ by Dr O’Meara. The Walker Art Centre and Coffee House Press have also endeavoured to answer this question with their Kickstarter project that has gathered a number of writers to explore concepts around the Internet Cat in an anthology that will be published in September 2015. Perhaps then we will be closer to understanding this Master of the Internet.

Where do you think our love for the Internet feline comes from?

October 19, 2014

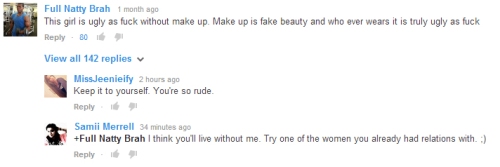

Anonymous Narcissists

Sites like 4chan are what Davison (2012) calls, ‘unrestricted’, and have a key focus around removal of authorship. Contrastingly, popular online platforms (such as Facebook, Google…etc.) continue a historical priority of attribution and authorship, concepts which are central to the ‘restricted web’. According to Davison, a removal of attribution allows for a more exploratory collaboration; but the anonymity attached to it also aligns itself to negative online behaviour, such as trolling. For Mandiberg (2012) the collaboration element of the unrestricted web allows users to create a personal media, that they are not just ‘“eyeballs” that can be owned’, but are rather charging their own creative desire. This agency combined with anonymity creates an uneasy coexistence within new media convergence.

4chan has also been described as ‘Pandora’s Box of the Internet’, where the ability of anonymity allows for gruesome and offensive content that can lead to offline mayhem (most notoriously via the /b/ forum, as explained in Mashable video above). With events such as the leaking of Jennifer Lawrence’s private images, hacking of Trayvon Martin’s email account, #CuttingForBieber twitter hoax (and more in this list); it’s easy to see the problems with 4chan, its anonymity and consequence-less attitude that fosters negative flak. However, with some morally awful actions, 4chan has also bestowed opportunities for moral gratification, such as the catching of animal abusers. 4chan’s founder, Christopher Poole, defends the anonymity aspect of this site as it fosters creativity and this can be seen through 4chan’s significant contribution to the Internet meme culture and online entertainment, such as: LOLcats (and Caturday); vocal talents of Tay Zonday; and Rickrolling.

Davison defines Internet memes as:

And that is the intent of the primarily visual culture on 4chan. It is a joke, it is intended to entertain. The site’s FAQs encourage positive contribution rather than ‘shitposting’, its aim is to create a humorous environment. For example in this screen grab below from a section of a transcript between Poole and a prosecuting lawyer, where the unique behaviour of 4chan users is discussed, we see that it needs to be made clear that certain online trends derived from 4chan are intended as a joke.

In this instance the cultural meme discussed also developed to become a form of social commentary, such as the public’s rickrolling of MTV Europe and the Anonymous movement first making headlines as it rickrolled the Church of Scientology.

The Anonymous vigilante (hacktivist) group that is now an internet institution in its own right was fostered out of 4chan’s message boards, where everyone who doesn’t choose to be identified is ‘anonymous’; and a large majority choose to be ‘anonymous’ (the nature of this anonymous culture that revels in their anonymity makes it difficult to get any concrete statistics around usage). This idea of everyone being unanimously anonymous starkly contrasts with the rising culture around selfies and digital narcissism. These contrasting ideas of online anonymity versus vanity, is explored by Palmer (2012) in his discussion on social space and our voluntary self-surveillance through the smart phone, which is intertwined with social anxieties around privacy. On one hand, we’re documenting and publishing our ‘performative self-representation’ and turning voyeurism into an entertainment form, but we’re also demanding the right to be forgotten and to be left digitally anonymous. In relation to 4chan this duality comes together under the idea of being an Anon — a publicly neutral identity. By posting anonymously you are not hiding, you are rather identifying yourself publicly as an Anon (this concept is best explained in this Tumblr post, “Faceless Together“).

For Davison, the key success of Internet memes and its cultural commentary (entertainment) is presented via the removal of attribution and authorship, which he calls the ‘nonattribution meme’. It is the ‘uncivilised’ wilderness of the Internet, the unrestricted web platforms, such as 4chan, which unmask cultural commentary that question human behaviour, nature and identity. And the divergence of this questioning has led to another institution – Anonymous – and the dynamic nature of the Internet will generate further. What do you think could spawn next?